Nuclear Brief April 2005

(updated July 14, 2005) Nuclear Brief April 2005

(updated July 14, 2005)

The Birth of a Nuclear Bomb: B61-11

The history of how the first U.S. post-testing nuclear

weapon, the B61-11, was developed and deployed has become clearer

following the partial declassification and released of a number of

documents by the

Department of Energy and Department of Defense under the Freedom of

Information Act. Plans to build more "modified" nuclear weapons make it

important to revisit how the B61-11 bomb was planned, approved, and

produced.

Before the Clinton administration initiated a

moratorium on nuclear weapons test explosions in 1992, such experiments

served mainly to develop and certify new nuclear weapons. Absent nuclear

testing, however, development of nuclear weapons in the future must rely mainly

on modification of existing designs and simulation. The B61-11 is the first such example

in what over the next decade will rebuild most or all of the warhead

types in the U.S. nuclear stockpile.

The B61-11 is significant because it is the first

post-testing modification and is significantly different than the weapon

it replaced. The B61-11 was first mentioned in public in September

1995 in "Stockpile Surveillance: Past and Future," a report published by

the three nuclear weapons laboratories. An obscure footnote on page 11

remarked:

"A modification of the B61 is expected to replace the B53 by

the year 2000. Since this modification of the B61 is not currently in

the stockpile, there is no Stockpile Evaluation data for it. The B61-7

data can be used to represent this weapon."

At that point the program had already been approved by

Congress and underway for two and a half years. After the lab report was

discovered by the

Los Alamos Study Group and the B61-11 program disclosed to the

public, DOE issued a

press release on September 20, 1995, which

explained that the B61-11 was not a new bomb but simply a

modified version of the existing B61-7 to replace the older and unsafe

B53. "There is no new mission," DOE assured.

"This is not new, in any way, shape or form," a DOE

official told Defense News in March 1997. General Eugene Habiger, then

command in chief of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) further explained:

"All we have done is put the components into a case-hardened steel shell

that has the capability of burrowing quite a ways underground, through

frozen tundra, through significant layers of concrete."

|

The B53

Nuclear Bomb |

|

|

The B61-11 officially replaced the B53, a

nine-megatons thermonuclear bomb first deployed in 1962. The

large yield could destroy facilities buried 750 feet (250

meters) underground. |

Nuclear Conception

The B61-11 program initially began on July 16, 1993, when then DOE

Deputy Assistant Secretary for Military Application (Defense Programs) Winford

Ellis "strongly recommended" to the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense

(Atomic Energy) Harold Smith that the B53 bomb be retired "at the

earliest possible date." The nine-megatons behemoth, first deployed in

1962, did not meet modern nuclear safety design criteria, DOE said.

A "Quick Look" study of alternatives to the B53 was

completed in December 1993 and cited a formal STRATCOM request for a

program to replace the bomb.

The government had known about safety issues in the B53

"for twenty years," Sandia Director Paul Robinson stated in 1997.

But the brute force of the weapon was considered the only means for

holding a few high-priority Soviet underground targets at risk, so

public safety was disregarded. Not until the late 1980s did the planners

consider replacing the B53 with an earth-penetrating weapon: the

Strategic Earth Penetrating Weapon (SEPW). The SEPW program, which

examined a spectrum of penetrator designs with relatively large nuclear

yields, advanced through Phase II before it was cancelled in 1990

(despite cancellation, some SEPW work continued as late as 1998).

Next on the nuclear drawing table was the W61, a

nuclear earth-penetrator warhead based on a retrofitted B61-7 bomb and

modified for delivery in a missile. The W61 was proposed as the warhead for the Tiger

(Terminal Guided and Extended-Range) II missile (later renamed Extended

Range Bomb (ERB), advanced tactical air-delivered weapon, TASM (Tactical

Air-to-Surface Weapon), and briefly the ALSOM (Air-Launched Stand-Off

Missile). The W61 program received Phase III authorization in 1990 as

an interim solution to the target set of the SEPW, but when the TASM was

canceled in 1992, the W61

was canceled as well, according to

a Sandia report.

|

B61-11

Chronology |

1993

Jul 16: Rear Admiral W. G. Ellis, DOE Defense Programs, asks ATSD(AE) to retire and

if necessary replace B53 "at the earliest possible date."

Dec 10: DOE Quick Look study identifies baseline design as

modified B61-7 with nose from cancelled W61 program.

1994

Sep 22: Nuclear Posture Review recommends B61-11.

Sep: PDD/NSC-30 directs development of B61-11.

Nov: B61-11 "B61-7 look-alike" concept developed.

Dec: SAF/AQQ, PEO/ST, XOF approve B61-11 concept.

1995

Jan 18: NWCSSC approves baseline design and recommends

approval.

Feb 6: Nuclear Weapons Council approves B61-11 concept.

Apr: Congressional committees are briefed.

Jul 18: Congress approves request to start B61-11

effort.

Jul: NWC asks Air Force to lead B61-11

Project Officers Group (POG) to implement project.

Jul: SAF formally tasks B61-11 POG to implement the project

and report back in 90 days.

Aug 2: Designers informed by DOE that Congress had approved.

Aug 4: DOE directs Albuquerque and National Labs to begin

work on the B61-11 program.

Aug 8: B61-11 Kick-off meeting held at Kirtland AFB.

Sep 1: First draft of Military Characteristics (MC) and

Stockpile to Target Sequence (STS).

Sep 6: DOE holds first all-agency B61-11 meeting. First time

people in production complex see the B61-11 concept.

Sep 8: First draft B61-11 MC circulated for comments.

Sep 15: Program authorized.

Sep: The B61-11 program is first mentioned in public.

Oct 3: SNLA/DOE proposes accelerating First Production Unit

by nine months from August 1997 to December 31, 1996.

Oct 18: B61-11 requirements finalized.

Nov 15: Harold Smith informs NWC that FPU should be

accelerated.

Nov 21: ATSD(AE) selects Option 2 (W61-like design) as

leading candidate and asks DOE to "devote full resources to

this design."

Dec: Final design selected.

1996

Feb: FPU delivery formally accelerated to December 31, 1996.

Apr: Harold Smith states that B61-11 could be "weapon of

choice" against Libya

Nov 20: Flight test certification passed.

Dec: B61-11 is accepted as "limited stockpile item" pending

further flight tests. 1997

Jan: First B61-11 enters stockpile.

Nov: The B61-11 enters service with the 509 Wing at Whiteman

AFB in Missouri. 1998

Oct: ALT 336 begins.

1999

Oct: ALT 349 begins.

2000

Sep: ALT 349 completed and certified.

Dec: ALT 349 recommended for acceptance to the NWCSSC.

Sandia led inter-agency group "to understand more fully the

weapon's penetration capabilities."

2001

The B61-11 was certified to meet all requirements, resulting

in its acceptance as a "standard stockpile item."

Dec 31: The Nuclear Posture Review Report states that the

B61-11 "has a very limited ground penetration capability"

and "cannot survive penetration into many types of terrain

in which hardened underground facilities are located."

2002

Jul: ALT 336 completed.

Oct: ALT 350 begins.

Phase

6.3 study begun for the refurbishment of the CSA

(secondary). 2005

Sep: ALT 350 completion expected.

Oct: ALT 357 start scheduled. 2008

Sep: ALT 357 completion expected. |

Managing Political Opposition

Building nuclear weapons was not popular in the early

1990s. After

disclosure

in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1992 that the DOE and nuclear

weapons laboratories were working on mini-nukes, Congress decided in

November 1993 � one month after the Air Force was asked to study the

B61-11 � to ban any "research and development which could lead to the

production by the United States of a new low-yield nuclear weapon,

including a precision low-yield nuclear weapon."

As a result, the B61-11 project � which was nicknamed

"The Duck" because it had identical flight characteristics to the

existing B61-7 bomb � was not submitted to the Nuclear Weapons Council

(NWC) for approval at the time. The Assistant Secretary of Defense for

International Security Policy (ASD/ISP)

was concerned that Congress

would not support it. Conveniently, the Congressional election in

November 1994 changed committee chairmanship to one more favorably

inclined to reopening the nuclear weapons production line, so the Assistant

Secretary of Defense "re-energized [the] project with a strong

recommendation that the effort be completed before Congress changed

again."

These events occurred at the same time that the

Clinton administration completed the Nuclear Posture review in September

1994. The NPR was widely portrayed as reducing the role of nuclear

weapons and Deputy Secretary of Defense John Deutch assured Congress

that "there is no requirement currently for the design of any new

warhead that we can see." He explained that "almost all" nuclear

modernization programs had been terminated. Some remained, one of which

was the B61-11. In fact, the the NPR Implementation Memo itself

specified the B53 be replaced by a modified B61-7 carried by the B-2.

Once the DOD was convinced that opposition in Congress

had eroded, things moved fast. The B61-11 project was submitted to the

NWC which approved it on February 6, 1995.

Meeting with congressional committees and their staffs

followed with

briefings given in

April 1995 to the

National Security/Defense and Energy and Water Development Subcommittees

of both the HAC/SAC and HNSC/SASC.

The initial contact to Congress was made to

Senators Ted Stevens and Daniel Inouye and Representatives C. W. (Bill)

Young and John P. Murtha. The DOE talking points did not mentioned the earth-penetrating

capability, but described the program as an effort to "improve the

overall safety posture of the nation's nuclear weapons stockpile." This

characterization was derived from the Nuclear Weapons Council decision

on the B61-11 program as being "in support of the President's decision (PDD/NSC-30)

to enhance the safety of the nation's nuclear weapons stockpile."

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) was also

briefed. On April 7, 1995, Robert Civiak, the Program Examiner in the OMB Energy and

Science division, was briefed by Jerry Freedman, Deputy Assistant to the

Secretary of Defense for Atomic Energy (Nuclear Matters), and Everet

Beckner, DOE Acting Secretary for Defense Programs.

Civiak indicated

that he wanted to understand what they were doing and "was a bit

'uneasy' with the potential for this to be viewed as 'developing a new

warhead.'" Freedman and Beckner assured that it was "not new warhead

development" and that "nuclear components are not being modified." The

meeting lasted only half an hour.

The justification for the B61-11 program was the need

to "improve the overall safety posture of the nation's nuclear weapons

stockpile," but DOE did not say explicitly say that the B53 was unsafe.

A

request for a $3.3 million reprogramming authorization in April

1995, for example, contained the cryptic sentence: "Although it is

currently safe...the B53 does not meet current safety criteria." The

purpose of the "replacement" program, the request stated, was to "avoid new warhead production."

No one argued with that, and on July 18, 1995 -- two years after the DOE and DOD began planning and

designing the B61-11 -- Congress officially approved production of the

nuclear earth-penetrator.

As so, less than two months after the United States with

a renewed pledge to nuclear disarmament ensured an unconditional

extension of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in May

1995, production of the B61-11 began.

The Work Officially Begins

DOD acted the same day Congress approved the B61-11 program.

The Nuclear Weapons Council (NWC) asked the Air Force to head the B61-11

Project Officer Group (POG) and the Secretary of the Air Force asked the

B61-11 POG to implement the project and brief the NWCSSC in 90 days on

status and milestones.

The DOD also formally asked DOE to join in the joint project to replace B53 with the B61-11.

DOE followed up on August 4 by issuing the guidance that directed Albuquerque Operations Office

and the National Laboratories to begin work on the B61-11 program. The

program guidance to the labs explained that the Air Force B61-11 POG would oversee the program, DOE Albuquerque

Operations Office would coordinate and lead the day-to-day field

activities, Los Alamos and Sandia would contribute as designers of the

B61 and roles in the POG, and Lawrence Livermore would provide peer

review of the development activities.

Many of the

characteristics of the B61-11 program were agreed to prior to

Congressional approval. During a

meeting on December 6, 1994,

for example, between the DOD, DOE, the Air Force, and the nuclear

labs (Sandia and Los Alamos), agreement was reached on modifying the B61-7

bomb, that the B-2 would be the carrier, and that the replacement

weapon would be chosen from four different design options. The

B83 bomb was also considered as a candidate, but B61-7 was chosen because it was the "most

mature" (note that for the RNEP, the DOE chose the B83 rather than the

B61).

The official

B61-11 kickoff meeting was held at Kirtland Air Force Base on August

8, 1995. The all-day meeting determined the program group structure and

the charter for each of the seven working groups: system engineering,

cost, testing, environments, logistic support, mission analysis, and

surety/reliability. At the meeting, the Air Force gave

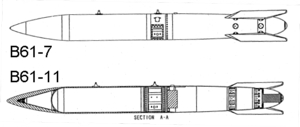

a briefing on the B61-11 program that summarized the milestones,

objectives for the meeting, and showed the following drawing of the

baseline conceptual design:

|

Initial

Illustration of B61 Conversion |

|

|

At the B61-11 kickoff meeting

on August 8, 1995, the Air Force presented this comparison

of the B61-7 (top) and the B61-11 bombs. The B61-11 design

was changed later in the program, adding a drag-cone to the

rear and more than 400 lbs to the weight. |

According to

the meeting minutes, the "baseline design meets weight, CG and roll

momentum requirements for the B61-7." The pitch and yaw were "about 10%

high," however, but "calculations indicate the delivery profile and CEP

will not be affected." The next step in the program would be development

of the Military Capability (MC) and Stockpile-to-Target-Sequence (STS)

documents as well as classification guidance for the weapon. MC and STS review was performed by an Environments Working Group

under the B61-11 POG to reflect

the "unique requirements of the B61-11."

The four different design options were based on four

different variables: mission capability, cost, B-2 risk, and

schedule/complexity. Mission capability was rated from "unsatisfactory"

to "best," and the other three variables were rated from "low to

highest." Trade-off was necessary if, for example, mission capability

was the best but the risk (read: program disturbance) to the carrier

high.

The progress of the B61-11 POG in determining which of

the options was best is evident from several briefings given in the fall

of 1995. In

the first briefing, given on September 29, the four

different design options are outlined and a notional plan for weapons

and aircraft testing stretching through June 1997. Although the briefing

includes values for cost, B-2 risk, and schedule/complexity, the mission

capability is not rated. That happened in

the

second briefing,

presented to Major General Joersz on October 23, which determined that

two of the four design options had an "unsatisfactory" mission

capability (see table).

The fact that unsatisfactory mission capability was an

issue in the design work was known even before Congress approved the

program. Shortly after approval was secured, DOE's B61-11 Program Manager at Oak

Ridge, Richard Cawood, remarked in an

interoffice memorandum

from August 1995 that the initial design definition for the B61-11 case and

associated hardware was "pretty soft and structurally adequate for only

soft targets. Now that the program appears to be secure perhaps they'll

get serious about the design," he remarked.

The October 23 briefing shows that "unsatisfactory"

mission capability was still an issue for two of the design options

three months later. Yet in

a briefing presented by Cawood that same month, one of the design

options appear to have been dropped leaving only three options for

further consideration. The three remaining options were all based on converting the B61-7, similar to the preliminary cost estimate

design, and involving modifying the "nose only."

|

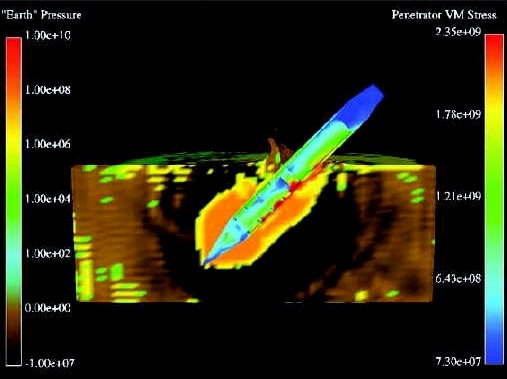

Computer

Simulation of B61-11 Impact |

|

|

|

Sandia National Laboratories performed

high-speed computer simulations to assess the stress on the B61-11

during impact in sand, soil, rock and permafrost. Two of the

initial design options had "unsatisfactory" mission

characteristics. |

Following a conversation on October with B61-11 Program

Manager at Sandia National Laboratories Don McCoy,

Cawood noted that McCoy expected the "structural case requirements

will firm up soon, perhaps by" October 13, 1995. "The design will be the

more robust of the three under consideration," Cawood noted, "with a

solid nose and with greater wall thickness."

Coinciding with the structural case requirements

firming up, the DOD suddenly

informed the NWCSSC on November 15 that delivery of the First

Production Unit (FPU) B61-11 should be moved up and "delivered as soon

as possible, with a goal of December 31, 1996." This was a considerable

change that squeezed production by eight months. The accelerated schedule involved reprogramming $3.3

million from within the DOE's atomic energy defense weapons activities

appropriations. Congress was informed but had no objections.

|

B61-11

Model Wind Tunnel Test |

|

|

|

A weapons engineer at Sandia National

Laboratories prepares a scaled-down model of a B61-11 for

aerodynamic testing in a wind tunnel. |

Moreover, DOD felt the design work had progressed

sufficiently to be able to select the option. On November 21, 1995, only

three months after the design work was officially begun,

Herald P. Smith

informed the Assistant

Secretary for Defense Programs at DOE, Victor H. Reis, that "Option 2

(full steel case) be chosen as the leading candidate."

Victor Reis replied on December 18, stating that DOE was "limiting

our development to the full steel case option (Option 2)."

In his reply letter, Reis also noted that he expected

Option 2 would be validated by "the safe separation analysis to be

released later this month." This concerned calculations performed by

Northrop, the producer of the B-2 bomber, to examine how B61-11 released

and cleared the aircraft. By the time Reis told Smith about the

validation, the calculations had already been successfully completed.

Northrop told Sandia about them on December 7, after which

Don McCoy at Sandia informed Cawood at DOE. McCoy said "this means

Option 2 (the W61-like design) is the selected design, although it won't

be official until" December 19, 1995.

|

The W61

Tiger II Missile |

|

Building on Other Designs

The "W61-like design" chosen for the B61-11 made

it

possible to base part of the B61-11 production on components and tools

developed for the W61 program. As mentioned above, the W61 was canceled

in 1992 when the missile intended to carry it was canceled.

The B61-11 steel case "was essentially the same case, used

for the W61 program." In fact, the B61-11 was so influenced by the

W61 that W61 classification guidance was

initially used until original classification authority was established

for the B61-11.

The B61-11 consisted of "field

retrofitting the B61-7 with a machines version of the W61 integral steel

case, removing the parachute and installing ballast aft of the bomb,

shortening the earth-penetrating nose, and installing a plastic...aeroshell covering to ensure identical

standard B61-7 geometry."

Some weapon components were manufactured based on the

design of W61 "blanks," but there was concern that "some of the W61

blanks will not yield an adequate product for the B61-11." This included

the Penetrator Case and the Threaded Ring components.

In addition to W61, the production of the B61-11 also

borrowed from another canceled nuclear program: the B90 nuclear

strike/depth bomb. Some of the tools developed for the B90 program were useable with some

modification for milling of internal features of the B61-11 case.

Production of the B61-11

The B61-11 program,

or the B53 Replacement Program as it was formally called, was

budgeted in 1995 to cost more almost $37.5 million, or $750.000 for

each of the 50 B61-11s produced. As the first post-testing weapons

production, the production program for the B61-11 program encountered

many "firsts" that required new or significantly changed production

methods.

Due to the very compressed production program, Product

Realization Teams (PRT) were not created. It was also the first regular production weapons program to

utilize a design process called WorkStream, a small-build program that

operate with small inventories for duration of the program. A

November 1995 overview of the Y-12 production commitment describes

many of the considerations that went into the B61-11 program and how the

producers anticipated to accomplish production.

The B61-7 conversion did not involve the Pantex

facility. Instead,

conversion kits were manufactured at the Nuclear Weapons Complex

facilities, principally at the Kansas City Plant and at the Y-12

plant in Oak Ridge. These conversion kits, which included both the

physics packages and the Canned Subassemblies (CSA), were then

disassembled from the B61-7 "in the field" and reassembled into the

earth-penetrator case by military personnel. Kit assembly took place

between January and December 1996, according to

a detailed DOE production plan. All B61-7s were taken from the active

stockpile.

Flight Testing

The choice of design Option 2 presented a problem due

to the number of flight tests required to certify the new design on the

B-2. There was no time and money in the existing B-2 flight test

program for the extensive testing required for a new weapon, so the B-52 was used to

conduct drop tests to certify that the B61-11 was

developed with identical properties and interfaces to the B61-7 which

was already certified on the B-2 (Block 20). This would limit the number

of flight tests required on the B-2. Moreover, to compensate for

addition flight testing costs to the B-2 program,

the B-2 program would be reimbursed up to $500,000 from

the B-52 flight test dollars.

|

B61-11

Drop Test |

|

|

|

A B61-11 drop test over the Utah Test and

Training Range (UTTR) shows use of rockets to control spin. |

Initially, weapons testing was scheduled for the

period between November 1995 and December 1996, followed by a four-month

aircraft testing period in March-June 1997. But due to the decision in

late 1995 to accelerate completion of the First Production Unit (FPU)

from August 1997 to December 1996, the initial testing program was cut

short. A total of 13 full-scale drop tests were performed in 1996,

three in Alaska and 10 at the Tonopah Test Range in Nevada. The

B61-11 passed its certification flight tests on November 20, 1996, in

time for completion of the FDU.

The frozen soil proof test in Alaska in 1996 was

cancelled due to an aircraft system failure on the B-2. The test was

rescheduled for march 1998, when two B61-11s were successfully dropped

by a B-2 bomber. Altogether, a total of 25 drop tests were

conducted from the B-2, B-52, B-1, and F-16. The drops tested the B61-11 earth-penetration

capability into sand, hardpan, compact soil, rock, concrete

and permafrost, indicating a wide geographic range for potential targets.

Stockpiling

Four

complete retrofit kits were delivered to the Air Force in mid-December

1996 and by the end of 1996, the B61-11 was accepted as a "limited

stockpile item" pending additional tests. The B61-11 officially entered operational service with the 509th

Wing at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri in November 1997.

The introduction into the stockpile coincided with the B-2 achieving nuclear Initial Operational Capability

(IOC) and replacing the B-1 in the SIOP-98 warplan. Air Combat Command (ACC)

informed the Defense Science Board Task Force on Nuclear Deterrence that

"integration of the B61/11 [sic] has introduced a vastly new means of

holding an enemy's buried, hardened and underground high-value targets

at risk." Approximately 50 B61-11s were produced.

|

B61-11

at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri |

|

|

A B61-11 shape on a loader inside a B-2

hangar at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri. The B61-11

entered service at Whiteman in November 1997, coinciding

with the B-2 replacing the B-1 in the SIOP.

Courtesy

nukephoto.com |

Although the B61-11 entered service

with the 509th Wing in November 1997, full certification of the

weapons took much longer. STRATCOM was concerned about mission

effectiveness and asked Sandia National Laboratories to provide

operational analysis and planning tools for the B61-11. This effort

included evaluating "fratricide concerns, optimizing delivery with

the B-2, and working to maximize both aircraft survivability and

weapon effectiveness." Not until 2001 was the B61-11 certified as a

"standard stockpile item" meeting all requirements.

Libya: The First B61-11 Target

Five months after Harold Smith called for an

acceleration of the B61-11 production schedule, he went public with

an assertion that the Air Force would use the B61-11 against Libya's

alleged underground chemical weapons plant at Tarhunah if the

President decided that the plant had to be destroyed. "We could not take [Tarhunah] out of commission using strictly

conventional weapons," Smith told the Associated Press.

The B61-11 "would be the nuclear weapon of

choice," he told Jane's

Defence Weekly.

Smith gave the statement during a breakfast interview with reporters after Defense

Secretary William Perry had earlier told a Senate Foreign Relations

Committee hearing on chemical or biological weapons that the U.S.

retained the option of using nuclear weapons against countries armed

with chemical and biological weapons.

The Pentagon

quickly retreated from the nuclear sable rattling. "There is no

consideration to using nuclear weapons [against Tarhunah], and any

implication that we would use nuclear weapons preemptively against

this plant is just wrong," said Pentagon spokesperson Ken Bacon. In

the same breath, however, Bacon said that Washington would not rule

out using nuclear weapons.

B61-11 Versus B53

The

B61-11 program was formally called a B53 replacement program, and government

officials have consistently portrayed the B61-11 as merely a "replacement" for the B53.

In doing so, the government

has insisted

that the B61-11 has "no new mission" but simply had to "fulfill the B53

mission." But it is difficult to find

any similarities between the B61-11 and B53. Indeed, a comparison of the two

weapons illustrate just how different they are and why the operational characteristics

of the B61-11 are so different compared with the B53:

|

B61-11

and B53 Comparison |

|

Characteristics |

B61-11 |

B53 |

|

Yield |

400 Kilotons |

9,000 Kilotons |

|

Dimensions |

12 ft x 13.4 in |

12 ft 4 in x 50 in |

|

Weight |

~1,200 lbs |

8,900 lbs |

|

Delivery platform |

B-2A (primary); also tested on B-1B, B-52H,

and F-16 |

B-52H |

|

Delivery mode |

Free fall, airburst, contact, laydown,

retarded, time delay, earth-penetration. |

Free fall, airburst, contact burst, only laydown delivery.

Timer armed and fired. |

|

Probability of arrival |

High (B-2A) |

Low to moderate |

Originally

built between 1962 and 1965, the B53s used to be carried by B-52 bombers

on continuous airborne alert missions between 1961 and 1968. Retirement

of the remaining B53s was underway in 1987 when the Reagan

administration suddenly announced it was curtailing retirement and

bringing retired (and still assembled) bombs back into the active

stockpile. The huge B53 apparently was needed to destroy a few

high-value Soviet underground facilities.

The B53 was highlighted as an unsafe weapon in the

1990 Drell Report, which contributed to the decision to replace the weapon.

The B53 did not have Command Disable (CD), PAL (Permissive Action Link),

or Insensitive High Explosives. Yet these features are also lacking in

warheads that are retained (W76 and W88), weapons that have not been

retired or replaced. Indeed, all remaining B53s in the

stockpile in 1993 were found to be "inherently one-point safe."

But the bomb did not have Enhanced Nuclear Detonation Safety (ENDS), intended

to prevent accidental firing, and was found to have "no assured level of

nuclear safety in a broad range of multiple abnormal environments."

Dismantlement operations at Pantex were authorized to begin in July

1994.

|

"Replacement" Improves Mission Flexibility |

|

|

|

The considerable difference is size

between the enormous B53 (right) and the B61-11

illustrates the operational gains from "replacing" the

old "earth-digger" with the new "earth-penetrator."

Whereas the B53 could only be carried on the veteran

B-52, the B61-11 is assigned to the B-2 stealth bomber

and has been test dropped from B-1B and F-16

aircraft as well. |

Safety was not the only reason for replacing the

B53. An

Air Force briefing from December 1994 indicates that nuclear

guidance issued by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff had been

changed and that the B-52 was no longer considered capable enough to

penetrate hostile air defenses on a nuclear bunker-buster mission with

the B53. The

Air Force briefing states that "a more survivable platform that a B-52

is needed" to "meet JSCP direction" and that the objective is to "increase

PA [Probability of Arrival] over target." The nuclear annex (Annex C) to

JSCP (Joint Strategic Capability Plan) 1993-1995 was updated three times

between July 1993 and the time of the Air Force briefing (December

1994).

Warhead Yield And Mission Adequacy

Many of the statements given by DOE and DOD on the

B61-11 program claim that no changes were made to the B61-7 warhead.

"This modification involves no change to the nuclear package of the

B61-7," DOE stated on September 20, 1995. Vice President for

National Security Programs at Sandia National Laboratories, Roger

Hagengruber, echoed in a television interview in 1997: "The physics

package itself is identical."

If "no change" and "identical" mean that the yield of

the B61-11 is the same as the B61-7, then these statements are false.

The B61-7 has several selective yields (possibly four) up to 360

kilotons. As of March 1996, the B61-11 was also expected to have this

capability, but at some point before March 2000 the yield was changed to

400 kilotons (a 10 percent increase). The selective yield options were

also canceled, making the B61-11 a single-yield weapon. This increase in yield may have been a result of the

limited earth-penetrating capability of the B61-11.

The frozen soil proof drop tests conducted in Alaska in March 1998

suggests that the earth-penetration capability of the B61-11 is

limited. During the test, two B61-11 shapes were dropped from a B-2 bomber at 8,000 feet. The two

shapes hit the ground some 45 feet (15 meters) from each other. The Air

Force said the B61-11 only proved capable of penetrating some 6-10

feet (2-3 meters) into the frozen

soil. At best the weapon would penetrate 15-25 feet (5-8 meters). A

photo taken of the retrieval of one of the bombs in Alaska suggests

the penetration depth was around 18 feet (6 meters).

|

B61-11 Test Drop In Alaska |

|

|

|

Two B61-11 shapes dropped by a B-2 bomber

into the Stuart Creek Impact Area near Fairbanks,

Alaska, on March 17, 1998. The weapons were retrieved,

indicating penetration depth of roughly 18 feet (6

meters) into frozen soil (left) and with intact front

casings but significant structural damage to the rear

section (right). |

Whether the drop tests prompted changes to the

design is unknown, but DOE initiated two alterations to the B61-11 in

1998 (ALT 336) and 1999 (ALT 349. Moreover, in 2000 Sandia National Laboratories

followed up with an inter-agency

study of the penetration capability of the B61-11. One year later,

in December 2001, the Bush administration's Nuclear

Posture Review informed Congress that the capability of the B61-11

was inadequate and incapable of holding at risk some deep and

hardened targets:

The B61-11 "cannot survive penetration into

many types of terrain in which hardened underground facilities

are located. Given these limitations, the targeting of a number

of hardened, underground facilities is limited to an attack

against surface features, which does not does not provide a high

probability of defeat of these important targets."

On the one hand this suggests that conversion of

the B61-7 into an earth-penetrator left significant issues

unresolved that the planners have been trying to resolve after the

B61-11 was rushed into the stockpile in 1997. On the other hand, it

suggests that the mission of the weapon has evolved since the

initial design was approved. Since the Air Force

determined in October 1995 that the B61-11

did "satisfy USSTRATCOM requirements," the NPR's determination

that that no longer is the case suggests that STRATCOM has changed

its requirements for the mission.

After ten years and tens of millions of dollars

spent on developing the B61-11, the Bush administration is now

trying to

persuade Congress that the solution to the unsatisfactory mission

capability of the B61-11 is to build yet another modified bomb: the Robust

Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP). The RNEP will be built around a

modified B83 very-high yield

bomb, the weapon that the B61-11 program rejected in favor of the

more "mature" B61-7.

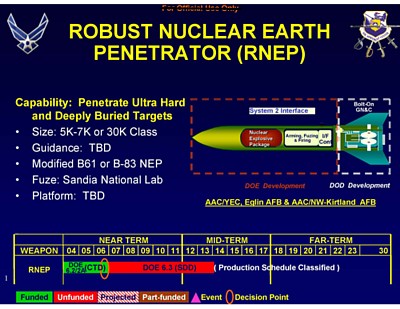

|

RNEP: The Follow-On To B61-11 |

|

|

The Bush administration plans to spend

$26 million on developing the Robust Nuclear Earth

Penetrator the next two years. Since this slide was

produced, a decision has been made to use the B83 bomb.

Compared with the 400 kiloton B61-11, the B83 has

selective yields up to 1.2 megatons. |

At the same time the Bush

administration is asking Congress to provide $26 million for RNEP in

2006-2007, new alterations continue to be added to the B61-11: ALT 350

for completion in September 2005 and ALT 357 (refurbishment of

secondaries) from October 2005 with completion in September 2008.

|